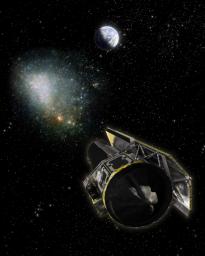

This artist's concept shows how astronomers use the unique orbit of NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and a depth-perceiving trick called parallax to determine the distance of dark planets, black holes and failed stars that lurk invisibly among us. These objects do not produce light, and are too faint to detect from Earth. However, astronomers can deduce their presence from the way they affect the light from background objects. When such a dark body passes in front of a bright star, its gravity warps the path of the star's light and causes it to brighten -- this process is called gravitational microlensing.

By comparing the "peak brightness" of the microlensing event from two perspectives -- Earth and Spitzer -- scientists can determine how far away the dark object is. Peak brightness is the moment when the observer, the dark object and background star are most closely aligned.

Humans naturally use parallax to determine distance -- this is commonly referred to as depth perception. In the case of humans, each eye sees the position of an object differently. The brain takes each eye's perspective, and instantaneously calculates how far away the object is. In space, astronomers can use the same trick to determine the distance of an invisible dark object.

In this illustration, the dark object is the moving black ball between Earth, Spitzer and our neighboring galaxy the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC; bottom right).

To determine the object's distance, astronomers observe the microlensing event at its "peak brightness" from Earth when the dark object crosses our line-of-sight (dashed line) to a given star in the SMC. This represents one perspective, like looking at an object with only your left eye.

To get the other "right eye" perspective, astronomers also observe the peak brightness with Spitzer when the object later moves through its line-of-sight. Because astronomers know the exact distance between Earth and Spitzer, they can determine the dark body's speed by timing how long it took for Spitzer to see peak brightness after astronomers observed the event on Earth. Using trigonometric equations and graphs to do the "brain's" job, scientists can infer the dark body's distance.

The scales in this diagram are greatly exaggerated for clarity. The distance between Spitzer and the Earth is miniscule in comparison to the distance to the dark object and SMC. Since microlensing events require extremely precise alignments, even such a tiny separation is enough to measure these objects out to tremendous distances.

Planetary Data System

Planetary Data System