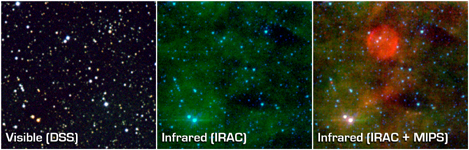

3-Panel Version

Figure 1

|  |  |

Visible (DSS)

Figure 2 | Infrared (IRAC)

Figure 3 | Infrared (IRAC + MIPS)

Figure 4 |

For the universe's biggest stars, even death is a show. Massive stars typically end their lives in explosive cataclysms, or supernovae, flinging abundant amounts of hot gas and radiation into outer space. Remnants of these dramatic deaths can linger for thousands of years and be easily detected by professional astronomers.

However, not all stars like attention. Thirty thousand light-years away in the Cepheus constellation, astronomers think they've found a massive star whose death barely made a peep. Remnants of this shy star's supernova would have gone completely unnoticed if the super-sensitive eyes of NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope hadn't accidentally stumbled upon it.

These three panels (figure 1) illustrate just how shy this star is. Unlike most supernova remnants, which are detectable at a variety of wavelengths ranging from radio to X-rays, this source only shows up in mid-infrared images taken by Spitzer's multiband imaging photometer. The remnant can be seen as a red-orange blob at the center of the picture (figure 4).

Although the visible-light (figure 2) and near-infrared (figure 3) images capture the exact same region of space, the source is completely invisible in both pictures. Astronomers suspect that the remnant's elusiveness is due to its location, away from our Milky Way galaxy's dusty main disk, which contains most of the galaxy's stars. A supernova is most noticeable when the material expelled during the star's furious death throes violently collides with surrounding dust. Since the shy star sits away from the galaxy's dusty and crowded disk, the hot gas and radiation it flung into space had little surrounding material to crash into. Thus, it is largely invisible at most wavelengths.

Spitzer's multiband imaging photometer did not need dust to see the remnant. The mid-infrared instrument was able to directly detect the oxygen-rich gas from the supernova's explosive death throes.

The visible-light (figure 2) image is a three-color composite of data from the California Institute of Technology's Digitized Sky Survey. In this image, light with a wavelength of 0.44 microns is represented as blue, 0.55-micron light is green, and 0.9-micron light is red.

The near-infrared (figure 3 ) image is a two-color composite of data from Spitzer's infrared array camera. In this image, starlight captured at 4.5 microns is represented in blue, and 8-micron light from dust is green. The far-infrared image (figure 4) combines the infrared array camera data with the multiband imaging photometer data, which show light of 24 microns in red.