|  |

| Annotated Image | Data Graph |

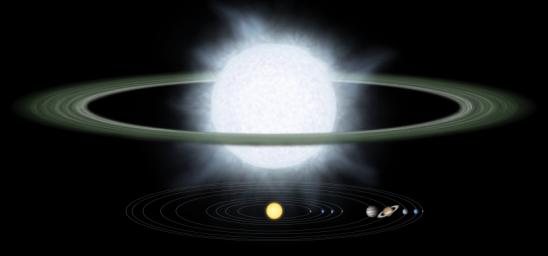

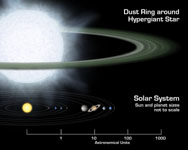

This illustration compares the size of a gargantuan star and its surrounding dusty disk (top) to that of our solar system. Monstrous disks like this one were discovered around two "hypergiant" stars by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope. Astronomers believe these disks might contain the early "seeds" of planets, or possibly leftover debris from planets that already formed.

The hypergiant stars, called R 66 and R 126, are located about 170,000 light-years away in our Milky Way's nearest neighbor galaxy, the Large Magellanic Cloud. The stars are about 100 times wider than the sun, or big enough to encompass an orbit equivalent to Earth's. The plump stars are heavy, at 30 and 70 times the mass of the sun, respectively. They are the most massive stars known to sport disks.

The disks themselves are also bloated, with masses equal to several Jupiters. The disks begin at a distance approximately 120 times greater than that between Earth and the sun, or 120 astronomical units, and terminate at a distance of about 2,500 astronomical units.

Hypergiant stars are the puffed-up, aging descendants of the most massive class of stars, called "O" stars. The stars are so massive that their cores ultimately collapse under their own weight, triggering incredible explosions called supernovae. If any planets circled near the stars during one of these blasts, they would most likely be destroyed.

The orbital distances in this picture are plotted on a logarithmic scale. This means that a given distance shown here represents proportionally larger actual distances as you move to the right. The sun and planets in our solar system have been scaled up in size for better viewing.

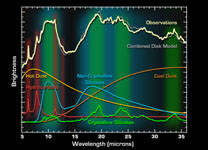

Little Dust Grains in Giant Stellar Disks

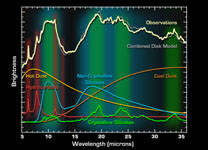

The graph above of data from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope shows the composition of a monstrous disk of what may be planet-forming dust circling the colossal "hypergiant" star called R 66. The disk contains complex organic molecules called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as well as silicate dust grains. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons can be found on Earth, in dirty barbeques and automobile exhaust pipes, among other places. They are thought to be necessary for primitive life to evolve. Silicates are essentially sand, and, in this case, were found in both their crystalline and non-crystalline, or amorphous, forms. The data were taken by Spitzer's infrared spectrometer, an instrument that spreads light apart into its basic parts like a prism turning sunlight into a rainbow. In this graph, or spectrum, light from the dust surrounding hypergiant R 66 is plotted according to its component wavelengths (white line). Astronomers determined the contents of this dust by creating a model (gray line) that best fits the observations. The model is the sum total of contributions from various types of dust grains (colored lines).

In addition to R 66, Spitzer made similar observations of a huge disk around the hypergiant star R 126, only this star's disk did not possess crystalline silicate grains. Both disks might represent either an early or late evolutionary phase of the planet-building process. In either scenario, the possible solar systems would be supersized, with host stars that are 30 and 70 times the mass of our sun, respectively.

Planetary Data System

Planetary Data System