- Original Caption Released with Image:

-

(Released 7 May 2002)

The Science

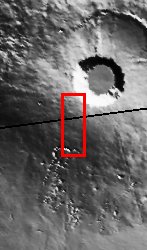

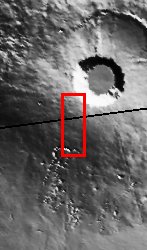

Four exceptionally large volcanoes in a region called Tharsis are unique to the western hemisphere of Mars. Three of the Tharsis volcanoes, Ascraeus Mons, Pavonis Mons, and Arsia Mons, are aligned along a NE - SW trend, with Pavonis in the middle, straddling the equator. Olympus Mons, the fourth Tharsis volcano and the largest in the solar system, is located NW of Pavonis Mons. At the top right of the image, the rim of the caldera of Pavonis Mons is just barely visible, with steep NE-facing cliffs formed by the collapse of a portion of the volcano's summit. At the southwest edge of the caldera, additional fractures are apparent and may someday collapse, making the summit caldera even larger. This image of Pavonis Mons also demonstrates some of the distinctive characteristics of the martian surface in the Tharsis region. Tharsis is very dusty; the dust covers everything like fresh snow, which is the reason why there is very little contrast in the surface materials as compared to other THEMIS images that show apparently bright and dark surfaces in the same picture. This dust cover makes it difficult to distinguish different geologic or geomorphic units in the area, and even the piles of lava flows that constructed this volcano are difficult to make out. Most of the craters on the volcano are small, a few tens of meters to kilometers in diameter, suggesting that this surface is a relatively young one on Mars (the older a surface is, the more and larger craters it has). In the lower third of the image, linear arrangements of small, round pits can be seen. These features are commonly called "pit chains" and most likely represent the collapse of lava tubes. Lava tubes are like a subway, allowing molten rock to move from place to place underground. A particularly large pit near the bottom center of the image looks a lot like a crater. However, the lack of degradation of the rim of this feature suggests that if it were an impact crater, it would be relatively young, and an ejecta blanket of debris should be visible. Because there is no apparent sign of an ejecta blanket, it is more likely that this and nearby similar features are simply the result of larger collapses.

The Story

Mars is Volcano Land, home to the largest volcanoes in the solar system. The small context image to the right shows a hole reminiscent of Darth Vader's Death Star, but it's really the sunken-in mouth of Pavonis Mons, one of three volcanoes that fall in a line across the Martian surface, almost like giant beads. You can see the very edge of this deep volcano hole at the uppermost righthand corner of the image. Deep fractures at the southwest edge of the caldera suggest that surrounding terrain might collapse, making the volcano depression even larger someday.

Except for this darker hole, the landscape looks rather drab and uniform in color. No wonderful black-and-white contrasts of terrain appear here as they do in many other THEMIS images. That's because dust in this area covers everything like fresh snow, giving the surface a smooth and unvaried look. Unfortunately, that makes it really hard for scientists to understand what different kinds of geologic features are present and what the lava flows are like. Usually, you can tell something about when each lava layer happened . . . but that depends on being able to see how each of the layers flowed over and under one another. That's not apparent here.

There are, however, some really cool features to study in this image. Deep, trenchlike tracings can be seen in the lower third of the image, as if a giant finger had scooped them out. So, how did they form?

When a volcano erupts, lava flows in rivers, finding narrow channels that make easy pathways down the slopes. Gradually, the surface of the flow becomes crusted over, and the molten lava is confined to a tube of its own making. Lava tubes are a little like a subway, allowing molten rock to move from place to place underground. When the lava stops flowing from its source and the rest of it drains out, what's left? Long, hollow lava-tube caves that slope down the volcano. Sometimes these lava tubes collapse, forming "pit chains" like the long depressions seen here.

While most of the round depressions in this image are craters, the large one near bottom center may fool you. Because it doesn't have a blanket of ejected material around it, its probably just a larger type "pit chain" collapse.

The craters that we do see in this image have their own story to tell. Since most of them are small, they reveal that the exposed Martian surface is probably much younger than in other places. Older surfaces are typically pitted by larger craters. That's because the planet was bombarded by much larger pieces of debris earlier in the formation of the solar system when more material was still "flying around." What this means is that the volcanic eruptions probably happened after the early stages of planetary bombardment, but not before all of the impacting material had a chance to make a lasting mark.

- Image Credit:

-

NASA/JPL/Arizona State University

Image Addition Date: -

2002-05-23

|

Planetary Data System

Planetary Data System