- Original Caption Released with Image:

-

(Released 16 April 2002)

The Science

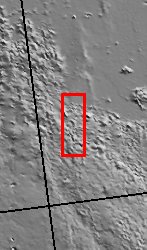

This THEMIS visible image was acquired near 11° N, 159° W (201° E) and shows examples of the remarkable variations that can be seen in the erosion of the Medusae Fossae Formation. This Formation is a soft, easily eroded deposit that extends for nearly 1,000 km along the equator of Mars. In this region, like many others throughout the Medusae Fossae Formation, the surface has been eroded by the wind into a series of linear ridges called yardangs. These ridges generally point in direction of the prevailing winds that carved them, and demonstrate the power of martian winds to erode the landscape of Mars. The easily eroded nature of the Medusae Fossae Formation suggests that it is composed of weakly cemented particles, and was most likely formed by the deposition of wind-blown dust or volcanic ash. Within this single image it is possible to see differing amounts of erosion and stripping of layers in the Medusae Fossae Formation. Near the bottom (southern) edge of the image a rock layer with a relatively smooth upper surface covers much of the image. Moving upwards (north) in the image this layer becomes more and more eroded. At first there are isolated regions where the smooth unit has been eroded to produce sets of parallel ridges and knobs. Further north these linear knobs increase in number, and only small, isolated patches of the smooth upper surface remain. Finally, at the top of the image, even the ridges have been removed, exposing the remarkably smooth top of hard, resistant layer below. This sequence of layers with differing hardness and resistance to erosion is common on Earth and on Mars, and suggests significant variations in the physical properties, composition, particle size, and/or cementation of these martian layers. As is common throughout the Medusae Fossae Formation, very few impact craters are visible, indicating that the surface exposed is relatively young, and that the process of erosion may be active today.

The Story

"Yardang!"

Now, that may seem like a peculiar-sounding curse word, but nobody would get in trouble for using it. A yardang is one of the very cool-sounding words geologists use to describe long, irregular features like the ones seen in this image. Yardangs are grooved, furrowed ridges that form as the wind erodes away weakly cemented material in the region. Rippling across the surface, yardangs tell the story of how the powerful Martian wind carved the surface into such a gorgeous pattern over time. (Don't miss clicking on the above image to see a detailed view, in which the beauty and almost dance-like symmetry of the waving terrain pops out in highly compelling, three-dimensional texture.)

It may be easy to see which way the wind blows in this area, since these streamlined features point in the direction of prevailing winds. But how can geologists understand the various kinds of terrain seen here? First, they have to study the different patterns of erosion, looking closely at how the wind has stripped off certain layers and not others.

Want to be a geologist yourself? Start at the bottom of the image and scroll upward, and see how the relatively smooth, higher terrain toward the south gradually becomes more and more eroded. Moving up the image, at first you?ll see only a few, isolated regions of parallel ridges and knolls. Go a little farther north with your eyes (toward the center of the image), and you?ll see how these linear knobs really get going! Once you get to the top of the image, only patches of these grooved ridges remain, leaving an incredibly smooth, wind-scrubbed surface behind. You know this layer has to be made of pretty hard material, because it seems impervious to further erosion.

Geologists studying Mars can compare these Martian yardangs to examples found on Earth, such as those in the Lut desert of Iran. Humans have even been known to use the wind as their inspiration, sculpting the shape of yardangs themselves. The famous sphynx at Giza in Egypt is thought to be a yardang that's been whittled down a little more by ancient human chiselers.

- Image Credit:

-

NASA/JPL/Arizona State University

Image Addition Date: -

2002-05-21

|