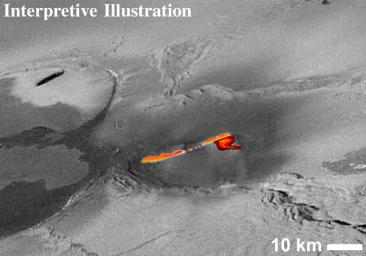

This mosaic of images collected by NASA's Galileo spacecraft on Thanksgiving Day, November 25, 1999 shows a fountain of lava spewing above the surface of Jupiter's moon Io.

In the original images, the active lava was hot enough to cause what the camera team describes as "bleeding" in Galileo's camera, caused when the camera's detector is so overloaded by the brightness of the target that electrons spill down across the detector. This showed up as a white blur in the original images. With the aid of computers, the whited-out area has been reconstructed to appear as it might without the "bleeding."

Most of the hot material is distributed along a wavy line which is interpreted to be hot lava shooting more than 1.5 kilometers (1-mile) high out of a long crack, or fissure, on the surface. There also appear to be additional hot areas below this line, suggesting that hot lava is flowing away from the fissure. Initial estimates of the lava temperature indicate that it is well above 1,000 Kelvin (1,300 Fahrenheit) and might even be hotter than 1,600 Kelvin (2,400 Fahrenheit).

These images were targeted to provide the first close-up view of a chain of huge calderas (large volcanic collapse pits). These calderas are some of the largest on Io and they dwarf other calderas across the solar system. At 290 by 100 kilometers (180 by 60 miles), this chain of calderas covers an area seven times larger than the largest caldera on the Earth. The new images show the complex nature of this giant caldera on Io, with smaller collapses occurring within the elongated caldera.

Also of great interest is the flat-topped mesa on the right. The scalloped margins are typical of a process geologists call "sapping," which occurs when erosion is caused by a fluid escaping from the base of a cliff. On Earth, such sapping features are caused by springs of groundwater. Similar features on Mars are one of the key pieces of evidence for past water on the Martian surface. However, on Io, the liquid is presumed to be pressurized sulfur dioxide. The liquid sulfur dioxide should change to a gas almost instantaneously upon reaching the near-vacuum of Io's surface, blasting away material at the base of the cliff. The sulfur dioxide gas eventually freezes out on the surface of Io in the form of a frost. As the frost is buried by later deposits, it can be heated and pressurized until it becomes a liquid. This liquid then flows out of the ground, completing Io's version of the "water cycle."

North is to the upper left of the picture and the Sun illuminates the surface from the lower left. The image, centered at 61.1 degrees latitude and 119.4 degrees longitude, covers an area approximately 300 by 75 kilometers (190-by-47 miles). The resolution is 185 meters (610 feet) per picture element. The image was taken at a range of 17,000 kilometers (11,000 miles) by Galileo's onboard camera.

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA manages the Galileo mission for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington, DC. JPL is a division of the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA.

This image and other images and data received from Galileo are posted on the Galileo mission home page at http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/galileo/. Background information and educational context for the images can be found at http://galileo.jpl.nasa.gov/gallery/io.cfm.

Planetary Data System

Planetary Data System