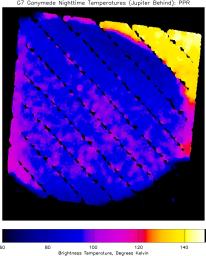

This infrared image of Jupiter's moon Ganymede, showing heat radiation from its surface at a wavelength of about 60 microns (millionths of a meter), provides the best view yet of nighttime temperatures on this hemisphere of Ganymede. Temperatures, derived from the brightness of the infrared radiation, can be determined from the colors by reference to the scale at the bottom of the image.

The image, taken by NASA's Galileo spacecraft, shows most of Ganymede's nighttime hemisphere, centered on longitude 180 degrees, with north at the top. Irregular, diagonal dark stripes result from missing data, and are not real. Part of Ganymede's illuminated crescent, warmed by the late afternoon sun and appearing pink in this representation (indicating temperatures near 110 Kelvin (-260 F), is visible in the lower left, but most of the part of Ganymede that is seen here is in darkness, glowing only because it retains some heat from the previous day. Jupiter appears in the background behind Ganymede in the upper right part of the image. Although it is nighttime on this part of Jupiter, the planet remains much warmer at night than Ganymede does, with temperatures near 140 Kelvin (- 207 F), because Jupiter's atmosphere is too dense to cool down significantly during the night, and is also warmed by heat that flows up from Jupiter's interior. The coldest parts of Ganymede that are visible (appearing dark blue) are near the north and south poles, and have temperatures below 80 Kelvin (-315 F), while parts of the equator remain at temperatures up to 100 K (-279 F) through the night, and appear in bright blue and purple colors. This same side of Ganymede was seen in full sunlight on Galileo's first orbit around Jupiter, and similar measurements showed that noontime temperatures at the equator reached 150 K (-190 F), which is 90 degrees (Fahrenheit) warmer than the night-time temperatures seen here.

The image was taken with Galileo's PPR (Photopolarimeter-Radiometer) instrument on the spacecraft's seventh orbit around Jupiter, from a range of about 65,000 kilometers (40,389 miles). Surface temperatures derived from the strength of infrared radiation, as was done here, are called "brightness temperatures," and may be slightly in error.

The PPR instrument builds up an image by slowly scanning across the target over a period of up to one hour. The motion of Galileo relative to Ganymede during this time causes distortions in the satellite shape on the image, which therefore appears slightly non-circular. The small overlapping circles that make up the image show the size of the area, about 160 kilometers (99 miles) across, covered by each individual PPR measurement. Blue spots in the dark sky in the lower right are due to noise.

JPL manages the Galileo mission for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington, D.C.

Planetary Data System

Planetary Data System