Figure 1

Click on the image for larger versionAn unusual, methane-free world is partially eclipsed by its star in this artist's concept. NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope has found evidence that a hot, Neptune-sized planet orbiting a star beyond our sun lacks methane -- an ingredient common to many planets in our own solar system.

Models of planetary atmospheres indicate that any world with the common mix of hydrogen, carbon and oxygen, and a temperature up to 1,000 Kelvin (1,340 degrees Fahrenheit) should have a large amount of methane and a small amount of carbon monoxide.

The planet illustrated here, called GJ 436b is about 800 Kelvin (or 980 degrees Fahrenheit) -- it was expected to have methane but Spitzer's observations showed it does not.

The finding demonstrates the diversity of exoplanets, and indicates that models of exoplanetary atmospheres need to be revised.

How to Measure Exoplanet Light

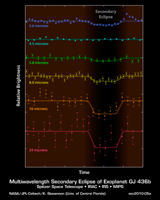

The plots in Figure 1 show light from the distant planet, GJ 436b, and its star, as measured at six different infrared wavelengths. Astronomers use telescopes like Spitzer to measure the direct light of distant worlds, called exoplanets, and learn more about chemicals in their atmospheres.

The technique involves measuring light from an exoplanet and its star before, during and after the planet circles behind the star. (The technique only works for those planets that happen to cross behind and in front of their stars as seen from our point of view on Earth.) When the planet disappears behind the star, the total light observed drops, as seen by the dips in these light curves. This same measurement is repeated at different wavelengths of light. In this graph, the different wavelengths are on the vertical axis, and time on the horizontal axis. Those dips in the total light tell astronomers exactly how much light is coming from the planet itself.

As the data demonstrate, the amount of light coming off a planet changes with different wavelengths. The differences are due to the temperature of a planet as well as its chemical makeup. In this case, astronomers were able to show that GJ 436b lacks the common planetary ingredient of methane.

Plot credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCF