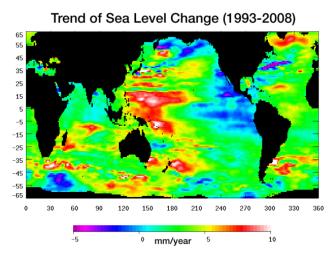

Warming water and melting land ice have raised global mean sea level 4.5 centimeters (1.7 inches) from 1993 to 2008. But the rise is by no means uniform. This image, created with sea surface height data from the Topex/Poseidon and Jason-1 satellites, shows exactly where sea level has changed during this time and how quickly these changes have occurred.

It's also a road map showing where the ocean currently stores the growing amount of heat it is absorbing from Earth's atmosphere and the heat it receives directly from the Sun. The warmer the water, the higher the sea surface rises. The location of heat in the ocean and its movement around the globe play a pivotal role in Earth's climate.

Light blue indicates areas in which sea level has remained relatively constant since 1993. White, red, and yellow are regions where sea levels have risen the most rapidly—up to 10 millimeters per year—and which contain the most heat. Green areas have also risen, but more moderately. Purple and dark blue show where sea levels have dropped, due to cooler water.

The dramatic variation in sea surface heights and heat content across the ocean are due to winds, currents and long-term changes in patterns of circulation. From 1993 to 2008, the largest area of rapidly rising sea levels and the greatest concentration of heat has been in the Pacific, which now shows the characteristics of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), a feature that can last 10 to 20 years or even longer.

In this "cool" phase, the PDO appears as a horseshoe-shaped pattern of warm water in the Western Pacific reaching from the far north to the Southern Ocean enclosing a large wedge of cool water with low sea surface heights in the eastern Pacific. This ocean/climate phenomenon may be caused by wind-driven Rossby waves. Thousands of kilometers long, these waves move from east to west on either side of the equator changing the distribution of water mass and heat.

This image of sea level trend also reveals a significant area of rising sea levels in the North Atlantic where sea levels are usually low. This large pool of rapidly rising warm water is evidence of a major change in ocean circulation. It signals a slow down in the sub-polar gyre, a counter-clockwise system of currents that loop between Ireland, Greenland and Newfoundland.

Such a change could have an impact on climate since the sub-polar gyre may be connected in some way to the nearby global thermohaline circulation, commonly known as the global conveyor belt. This is the slow-moving circulation in which water sinks in the North Atlantic at different locations around the sub-polar gyre, spreads south, travels around the globe, and slowly up-wells to the surface before returning around the southern tip of Africa. Then it winds its way through the surface currents in the Atlantic and eventually comes back to the North Atlantic.

It is unclear if the weakening of the North Atlantic sub-polar gyre is part of a natural cycle or related to global warming.

This image was made possible by the detailed record of sea surface height measurements begun by Topex/Poseidon and continued by Jason-1. The recently launched Ocean Surface Topography Mission on the Jason-2 satellite (OSTM/Jason-2) will soon take over this responsibility from Jason-1. The older satellite will move alongside OSTM/Jason-2 and continue to measure sea surface height on an adjacent ground track for as long as it is in good health.

Topex/Poseidon and Jason-1 are joint missions of NASA and the French space agency, CNES. OSTM/Jason-2 is collaboration between NASA; the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; CNES; and the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites. JPL manages the U.S. portion of the missions for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C.

Planetary Data System

Planetary Data System